Laika Was Crazy Enough To Animate A 16-Foot Tall Skeleton for ‘Kubo and The Two Strings’

Of all the many achievements in Laika’s newest stop-motion animated adventure, Kubo and the Two Strings, opening today in U.S. theaters, clearly the biggest is the Giant Skeleton.

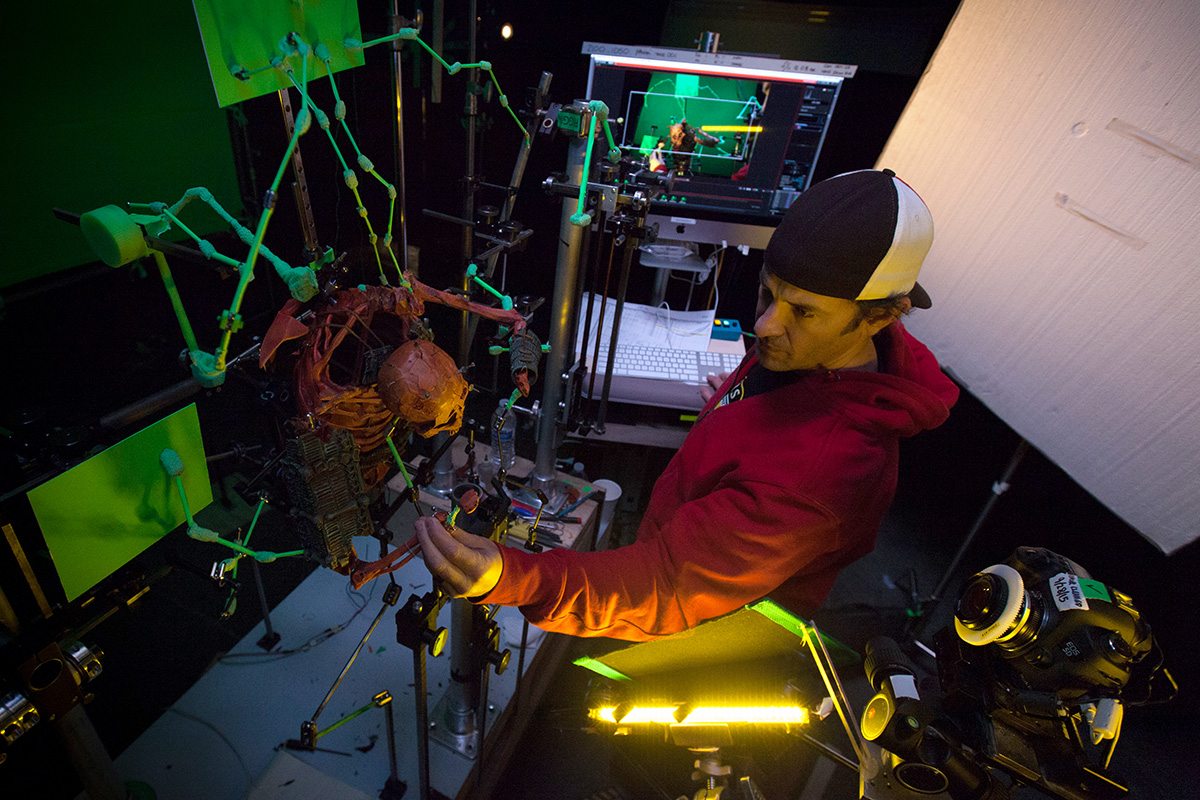

Sixteen feet tall and weighing 400 pounds, the skeleton is considered by the studio to be the largest stop motion puppet ever made. It required extensive planning, design, build, and animation phases—even a giant mechanical robot was considered to operate it—plus a major visual effects effort to place the skeleton in its home, the Hall of Bones. Cartoon Brew explores the ‘insane’ idea to build and animate the skeleton, and how Laika actually went through with it.

Skeleton Outline: Full Scale and Fully Stop Motion

In the Travis Knight-directed film, the Giant Skeleton torments the main characters Kubo, Monkey, and Beetle, inside its Hall of Bones lair. Laika’s original plan was to build a smaller scale skeleton puppet and perhaps some larger hand or leg pieces, and then make smaller versions of the other characters to animate during the sequence.

The problem was, the animators did not necessarily like the idea of having to deal with the surrounding smaller puppets that interact with the Giant Skeleton. “They were only going to be an inch-and-a-half tall with no real armature in them—just a blob of foam that didn’t pose well,” explained Steve Switaj, Laika’s lead camera and motion control engineer, at a recent Kubo presentation at SIGGRAPH.

This initial concern about fidelity was then compounded when the storyboards for the sequence became even more dynamic, suggesting that the puppets would require more close-ups and more exotic stunts. Eventually in one of Laika’s early meetings, someone suggested they just build the full-sized skeleton and then animate the other puppets around it at the original scale. “And hence, the seed of insanity, was planted,” said Switaj.

Any question of the skeleton being a large-scale CG object was never seriously considered, even though Laika has readily adopt a hybrid mix of practical stop motion puppets and visual effects in all of its recent films.

“Time and again I am amazed by the solutions that the rigging, camera, and animation teams would present,” Laika visual effects supervisor Steve Emerson said in an interview with Cartoon Brew. “Absolutely the skeleton could have been CG. But when you’re in a room surrounded by artists that you love and respect and there is an overwhelming enthusiasm about the idea of building the largest stop motion puppet that has ever been created—and everyone is convinced we can pull it off—I want to support that spirit and enthusiasm in whatever way I can.”

OK, Now We Have To Actually Build It

Laika had built large puppets before, specifically the five-foot Mecha-Drill from The Boxtrolls. But the Giant Skeleton was something else; it was larger, heavier, and needed to be animated as precisely as possible.

The first step in realizing the build, then, would be to have the skeleton manufactured by the rigging department—usually responsible for large props or things that move in Laika films—rather than the traditional puppet building department that relies on hand-crafted and 3D printing techniques. Rigging also collaborated with the art department which would design and also dress the final skeleton puppet.

Having mastered the art of rapid prototyping and 3D printing for its smaller-sized stop motion puppets, Laika had to abandon those methods for the Giant Skeleton. Or so they thought. It turned out there were companies that could print and cut high-density industrial foam into any form, which had the added benefit of being as light as possible. This was used in particular for the skeleton ribs, while other parts relied on more of a papier-mâché approach.

Traditional stainless steel armatures and nylon interiors were also out of the question due to weight. So the creature was split into two sections—the torso (including the head, ribs, and arms) and the legs. Still, the 400-pound torso and its 20-foot wingspan had to be animated. But instead of the traditional ball joints that might be used on stop motion puppets, a series of magnets were used to fix the arms and head to a skeleton torso. The skeleton’s surface was designed to be the remnants of those it has killed, and featured over 1,000 bone shapes. Around 70 unique swords were made for the skull.

OK, Now We Have To Actually Move It

The Giant Skeleton was not only huge, it had to be manipulated, frame-by-frame. Getting such a large puppet to emote in a smooth manner while ensuring arms and areas of the skeleton were as rigid as possible between manipulations was going to be crucial. So Laika embarked on some R&D to find out the best possible—and affordable—way to move its biggest creation.

The first mechanism considered was a motion control system, something the studio had intimate knowledge of. One had also been used to move the Boxtrolls’ Mecha-Drill. But the skeleton was just so heavy, said Switaj, that a motion control rig was not going to cut it. Laika needed a powerful mechanical arm that could pick up the skeleton puppet and move it around.

“The thought that ran through our heads was, of course, giant-ass robot!,” recalled Switaj. A working industrial factory robot with a manipulator arm was even sourced from eBay, but quickly discounted when it was realized the interface for such robots was bespoke and could not be plugged into Laika’s existing systems.

The answer lay, instead, in motion bases or hexapods typically used in amusement park rides or as film special effects gimbals, say for a boat at sea or a helicopter stunt. Laika ultimately designed and built its own hexapod, a six-axis actuator that enabled the torso to be moved. “Controlled by a custom-made jog box, five actuators moved the twist, tilt in all directions and x, y and z,” Laika animation supervisor Brad Schiff told Cartoon Brew. “This way the movement was easily controllable. Finite and precise.”

Meanwhile, a separate system was devised for the skeleton hands and arms. The arms, weighing six pounds each, were also too heavy to be supported only by a metal interior; thus they were supported by a cradle of cables and pulleys above the stage. Each cable was controlled by a robot-operated stepper motor that moved the arm and elbow into place.

More Than Just Moving: The Animation Process

Next came some further research and development to enable animators to creatively bring the Giant Skeleton to life via stop motion. At first, Laika wanted to provide a simple input device an animator could carry while also moving around the structure on an elevated platform.

“We thought about making an input device that was really complicated in the shape of a human being,” said Switaj. “But we ended up with something that was the size and shape of a normal puppet. Animators are used to leaning over and grabbing the head and twisting it or grabbing the body and twisting some winders, so it worked very well.”

Animator Charles Greenfield was charged with climbing around the skeleton and operating the input controller. It worked by sending data first through to the motion control camera system (a Cooper setup Laika uses for photographing its stop motion puppets). Here too, the studio had to write a special program to enable the Cooper to talk to the hexapod—“We had to make the world’s only giant-skeleton-to-USB-adapter,” joked Switaj. When instructed, the hexapod actuators would then move the puppet.

On a given shot, this is how the skeleton animation worked. The animator would place his hands on the puppet which would be detected by the system. This unlocked everything and allowed the movement input by the animator to be tracked. When the animator let go, the sensors detected that occurrence and every moving part was locked for photography.

“This certainly took some getting used to because of its cumbersome nature,” admitted Schiff. “It wasn’t quite as precise as we typically like, but Charles, tamer of this beast, figured it out. He mastered how to get the finite movement necessary to make it move naturally and feel like the giant it needed to be.”

For the skull animation, the eyes and jaw were hand-manipulated. Just like a smaller puppet, the animator relied on x-sheets to figure out the timing of his poses but had to make the movements bigger in nature. And although the Giant Skeleton was a huge build, it was also done in conjunction with a smaller scale (but still significantly-sized) one-sixth-scale skeleton puppet coming in at 2.5 feet tall. The 16-foot version took six months to construct and was filmed with for a year. The result: 49.2 seconds of footage.

When Stop Motion Meets CG

For all its practical puppetry, the entire Hall of Bones sequence still relied on extensive visual effects work. Laika does not shy away from this—in some ways the studio treats the stop motion portion of the animation like a live action film, often capturing puppets against greenscreen and incorporating other digital characters, environments, atmosphere, and other effects into the scene.

For the Hall of Bones itself, the visual effects team added to an existing ground plane and wall section with matching CG environments. All the usual live action approaches to replicating these pieces in CG were followed, including high dynamic range reference photographs. The vfx team also stepped in with a raft of ‘invisible’ effects fixes, such as the removal of cables and supports, compositing work, and frame-by-frame painting.

That hybrid approach has perhaps become Laika’s calling card; indeed in many shots it’s not always clear what is real and what is CG. “As far as where we can mix things,” said Emerson, “we always want to make sure that hero or main characters are physical puppets that are being hand animated. Anything that they touch or interact with, be it a prop, another character or a ground plane, is always physical. But once we move away from that region of interest, if CG makes sense, we’re not afraid of it.”