Ottawa Animation Festival 40th Anniversary Look-Back: ‘Two Sisters’

The Ottawa International Animation Festival, North America’s largest and most significant animation event, celebrates its 40th anniversary this year.

In honor of that occasion, the festival has commissioned a number of international animation historians, programmers and critics to write essays about each of its grand prize-winning films. In partnership with the festival, Cartoon Brew will present one essay per week leading up to the festival on September 21-25, 2016. We’ve already presented essays on The Man Who Planted Trees and Hen, His Wife, and today, we continue with the 1992 winner, Two Sisters directed by Caroline Leaf.

For more information on attending Ottawa, visit animationfestival.ca.

Ottawa 92 Winner: Two Sisters

Essay by Kelly Gallagher

Caroline Leaf’s powerful and significant direct animation, Two Sisters (1991), is a momentous celebration of the work of women’s hands.

The animation itself tells the story of two sisters, Marie and Viola, who live in solitude on an island, caring for each other while closed off to the outside world. A stranger comes to visit one day, completely disrupting their isolation and daily rhythms, throwing them into panic.

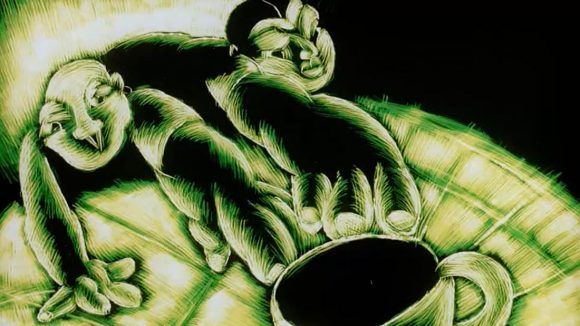

The animation process involved Leaf directly etching into 70mm film emulsion to create the illustrated images. There is a violence to carving—to cutting into something and pushing it aside. And in the case of film emulsion, this violence of carving is what eventually lets light shine through (literally, when film is projected). Both Leaf’s animation process and the animated story of Marie and Viola deeply investigate the power of women’s hands in conveying experience, experiencing life itself, and the role of strength in letting the light “in” and “through.”

Almost every shot of the entire film includes a detailed look at characters’ hands. From the opening shot of the stranger’s hands and fingers swimming through the blue waters and reaching and extending out towards us, to the final scene of Marie grasping the keys to the house while Viola’s hands rapidly type away, hands are continually at the visual fore, front and center within the frame. From the opening scene of the stranger, we cut to Marie’s hands lovingly brushing Viola’s hair, and later pouring coffee. We see Viola’s hands fiercely typing away and are made aware that she is a writer. Marie and Viola’s hands often consume the entirety of the frame, and every single joint and small finger gesture is magnified for us.

Just as we see Viola, the writer, leaving her mark through typing, we too see Leaf’s marks made for us on screen. The film is creating a space for us to reflect on the woman artist’s labor behind the book (and film). Leaf’s hands etching away at the film emulsion allows us to see Viola’s typing, punching her own marks and inscriptions into paper. The harnessed and fierce power of women’s hands and collaboration allows women’s mark-making and experience-sharing to regenerate and thrive. Both Leaf and Viola’s hands communicate with each other, violently, lovingly, carefully. Meanwhile Marie’s hands convey the invisible and domestic reproductive labor of women as she cares for Viola, cooks, cleans, and keeps the house “in order.”

The power of women’s hands as a true force is exemplified through the harsh sounds of Viola’s typewriter, accompanying her etched and magnified gestural fingers and knuckles typing away so fiercely as if almost to break the vessel through which she communicates to the outside world. Viola types away violently and seemingly into a catharsis—the repetitive movements of her fingers, sharing experience with others.

It is impossible not to contemplate on the repetitive (and sometimes cathartic) movement of the process of animation itself, sculpted out for us by Leaf, moving us forward in time, frame by frame. Because the 70mm film was re-photographed, we are not rushed through the animation at 24 illustrations per second, but rather given the space to swim in the light, which took Caroline Leaf a year and a half to design for us.

At the climactic moment when the stranger reaches the house of Viola and Marie, he enters an unlocked door throwing the sisters into a fit of panic. We learn that Marie is especially upset since she has kept Viola in isolation from the outside world because of Viola’s facial disfigurement and fear of how the world would react.

The stranger states he simply wants to meet Viola, as she is the author behind his favorite books. Viola reveals herself and her face to him before turning away and covering her face with her hands in shame. The stranger’s hand reaches out to Viola. His left hand moves Viola’s own hands away from her face, allowing her face to come into the light and be seen. His right hand intimately embraces Viola’s face, as he is in awe that he has the privilege of looking upon his most beloved author.

The importance of the hand as a site of power continues to be emphasized further through these electrically charged moments of embrace. Later on, Viola’s hand holds Marie’s face while Marie’s hands then grasp Viola’s as she kisses them. The hand not only leaves its mark of experience (Viola’s typing), but also experiences life itself—tactilely, tangibly, touching, feeling, learning, and connecting with others.

The stranger invites Viola to step outside into the light. For what must be the first time in a long time, Viola steps outside and is subsumed by the bright glowing warm light of the sun. The film emulsion, etched aside, inviting and letting through the warm light of the projector. Viola signs her admirer’s copy of her book: “To the stranger who sees me in sunlight.” It is the carved away film emulsion on the celluloid that allows the audience to see Viola as well. Light itself makes the process of direct animation possible and allows us into the lives of these sisters.

Viola makes her way back inside and the sisters are back as they were at the start of the film, yet something within them both has shifted and transformed. Viola is typing away ferociously and Marie sits in her rocking chair, holding on tight to her house key. Fingers grasping and embracing the key illustrate for us the direct correlation between the two. Women’s hands in (and behind) Caroline Leaf’s Two Sisters are the key to sharing one’s experience, leaving one’s mark, tangibly experiencing life, and connecting to others.