Victor Haboush (1924-2009)

Victor Haboush passed away on May 24, 2009 at age 85. A first-generation American of Lebanese descent, he was born on April 16, 1924 and grew up in Indianapolis, Indiana.

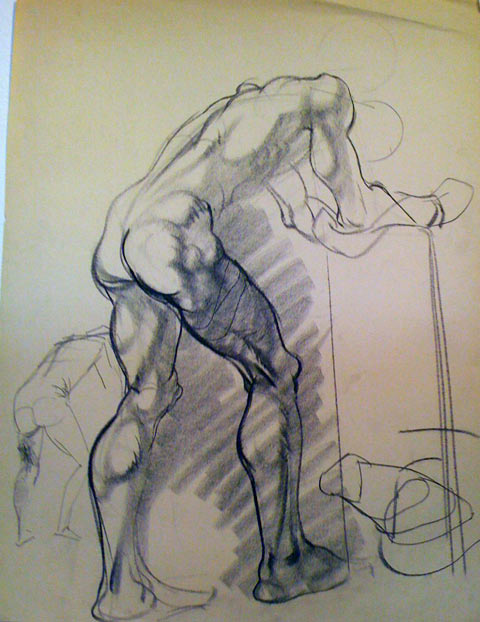

During World War II, he took part in the D-Day landings at Normandy as a member of the Coast Guard, and later served in the Pacific theater. (His brother was mortally wounded at Leyte.) Following the War, he attended Art Center College of Design on the G.I. Bill where he studied extensively with Lorser Feitelson.

On the recommendation of his Art Center classmate Eyvind Earle, he was hired at Disney in 1952 to help finish layout on Peter Pan. His first association with Disney came earlier, when he helped Earle draw this Golden Book adaptation of Peter Pan. He built up an impressive list of credits at the studio including assistant art direction on Melody and Toot Whistle Plunk and Boom, and layout on Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty and 101 Dalmatians.

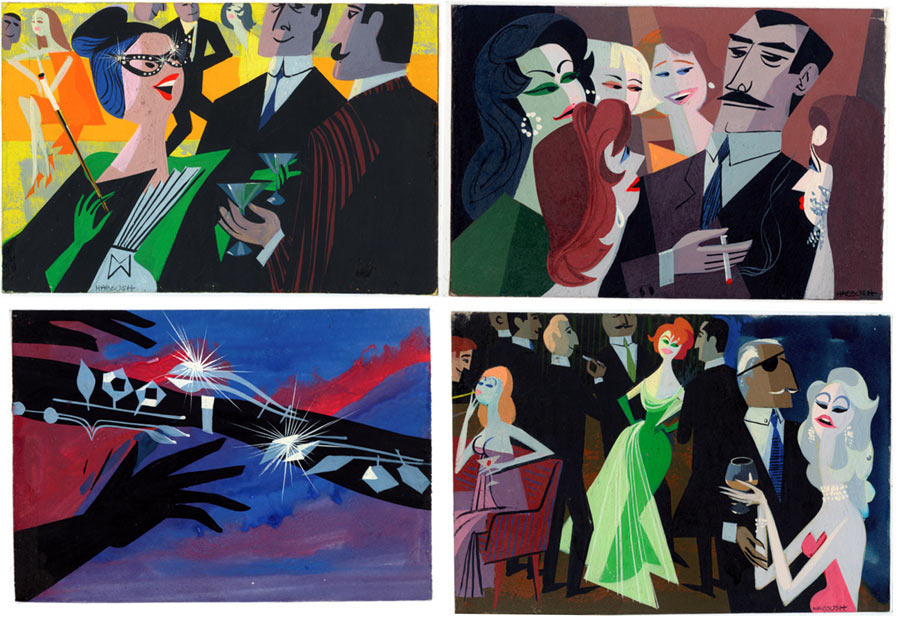

Vic was one of Tom Oreb’s closest colleagues during the 1950s and they worked together as a team, especially in Disney’s TV commercial unit. The characters in this Cheerios ad were styled by Oreb with background layout by Vic:

He described to me in 2000 his relationship with Oreb:

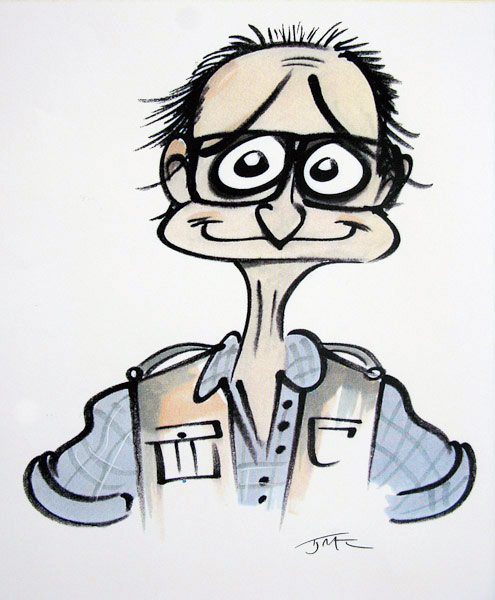

“Eyvind [Earle] and I were the two hot new guys, and we developed a lot of people not liking us. We’d work on the weekends, we’d throw storyboards up…a lot of the old guys just absolutely turned on us. It was really kind of brutal in a way. But guys like Tommy [Oreb], Ward Kimball, Bill Peet, Don DaGradi, they didn’t have that closed kind of thing. Tommy really married Eyvind and I. He became our friend. He looked after us. He talked us up. So the three of us became really good friends. We started hanging out together and all of that. Eyvind was kind of like Tom’s equal. They were both in the same age range. And I was the young kid. I was probably nine nor ten years younger than both of them. I just became Tom’s protege. I idolized him.”

When Oreb left Disney to work at John Sutherland Productions, Vic followed, and they worked together on films like Destination Earth and The Littlest Giant.

They both soon returned to Disney to finish Sleeping Beauty, where Vic played a key role in designing the “Thorn Forest” sequence. In an interview, he spoke about his work on the sequence:

“I saw these awful drawings of the Thorn Forest, these big huge thorns, and it was a big mess. Basil Davidovich told me, ‘Vic, Woolie [Reitherman] doesn’t want anybody working on it anymore.’ But I went ahead anyways and spent the next three weeks working on this sequence. Everybody’s kind of laughing because they know that Woolie’s going to be pissed off when he sees that I’ve wasted all that time on it. The problem is that when you draw a vine, it gets smaller as it’s coming towards you, and that destroyed perspective. I worked it out where the vine overlapped itself so as it came towards you, it would be coming in front of itself and that created the depth. So I see Woolie one day and I say, ‘Woolie, I’ve solved the thorn forest,’ and he says surprised, ‘What! We should be finished with that.’ I take the work to show him in his office and he looked at them and pushed them aside. I thought ‘Oh no, here it comes,’ and he says, ‘Haboush, these are wonderful. From now on you’re the thorn forest guy.’ For the next three months, all I did was draw those stupid thorns. Bill Peet would come in and say, ‘Vic, nickel a thorn, charge a nickel a thorn, don’t ask for a raise, just get a nickel a thorn.'”

Vic worked at numerous other animation studios besides Disney, including Quartet Films, early seasons of The Flintstones and The Jetsons at Hanna-Barbera, and The Incredible Mr. Limpet at Warner Bros. He was the art director of UPA’s second feature Gay Purr-ee as well as the Mr. Magoo and Dick Tracy TV series.

He told me that one of the most embarrassing moments in his career was during a short film screening at the Academy. UPA owner Henry Saperstein had submitted one of the Dick Tracy episodes for Oscar consideration, and when Vic’s name appeared onscreen as art director, he shrunk low into his seat. Working on the inferior UPA TV shows made him realize the direction the animation industry was headed and he resolved to set out on his own. In the early-1960s, he launched a studio, Spungbuggy Works, in partnership with animator Herb Stott and storyman/designer/all-around creative dynamo John Dunn. It was at this studio that he worked with Dunn to develop numerous feature and TV concepts, many of which would be later produced by Friz Freleng, who lured Dunn to his studio DePatie-Freleng.

In the mid-1960s, Vic left animation and shifted into live-action. He started his own studio, Victor Haboush & Associates, which later became The Haboush Company. Over the next thirty years, he directed and photographed over 1,500 commecials, winning numerous Cannes Gold and Silver Lions, Clios and IBAs.

His campaigns included the Kibbles N’ Bits “The Hook” campaign, numerous commercials featuring Ronald McDonald for McDonald’s, the Taco Bell “Crashing Bell” series, the Hefty Bag series with Jonathan Winters, early Keebler Cookies spots, and the Schlitz Malt Liquor “Bull” campaign.

One of his former producers Paul Babb said, “Vic was one of the go-to guys in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s for commercials…He was no businessman but he was an incredible artist–and not just as a director. Try putting a pencil or a paintbrush in his hand, sit back and wait for something remarkable.” Vic might have agreed with the sentiment that he wasn’t an expert businessman. He knew how to sell an idea and he knew how to execute, but he was more interested in achieving a quality result than heeding the bottom line. He often told me that his studio wouldn’t have lasted had it not been for his brother, who served as his producer for many years.

Jon Derovan, who was Vic’s producer during the final decade of his career, told Shoot magazine, “Victor allowed me to be a creative producer. He brought me into the creative process beyond the nuts and bolts of the business….He was generous. He was open to good ideas no matter where they came from–and he was quick to credit the person who came up with the idea. He would never take credit for an idea that wasn’t his.”

Even while he ran the studio, he remained connected to animation and art. He employed many animators over the years including John Kimball, Robert Swarthe, Dale Case, and the unheralded Robert Mitchell. Through his company, Vic produced three shorts directed by Mitchell–K-9000: A Space Oddity (1968), the Oscar-nominated The Further Adventures of Uncle Sam (1970), and Free (1972). His company also produced another art film, Paint (1968) directed by Norm Gollin and starring LA airbrush pioneer Charlie White.

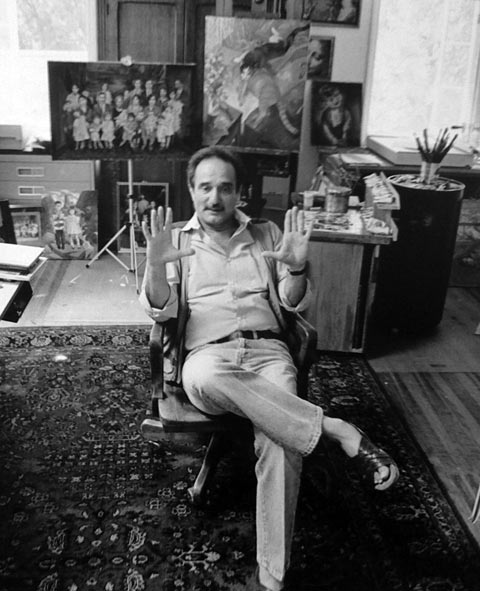

I first met Vic around the year 2000 while I was researching the life of Tom Oreb. By this time, Vic had retired from filmmaking and was painting full-time. We hit it off and formed a friendship that endured until his death.

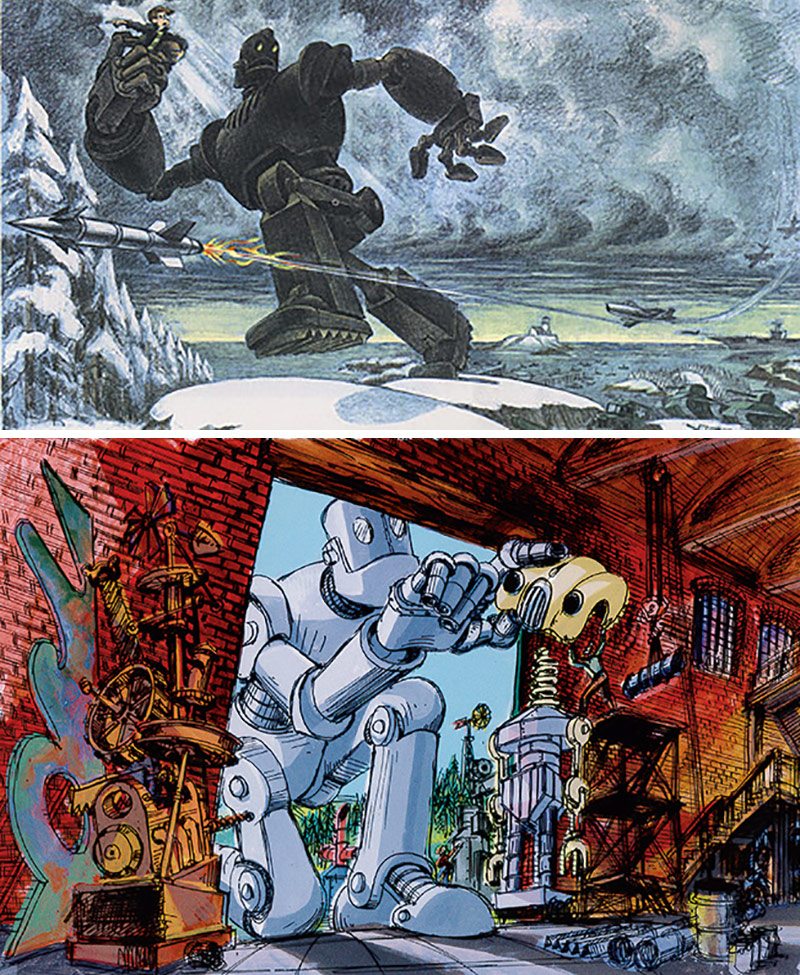

Vic’s attitude towards life was different from the majority of older people I’ve encountered. He was young at heart, with an insatiable curiosity about the world around him and a flexible thought process. His opinions about different artists evolved over time, much like his distinctive painting process, which often involved reworking an image dozens of times until he was satisfied. He refused to live in the past. Whenever we would get together, he couldn’t wait to discuss people he’d recently met, a new place he had visited, or a new book he’d read. He was as enthusiastic about younger artists as he was appreciative of veteran artistic colleagues. When he returned to animation one final time as a development artist on The Iron Giant, he became enamored with artists like Mark Whiting and Teddy Newton, the latter whose work he felt was some of the freshest he’d seen in a long time.

To fully appreciate Vic, you had to know him in person. Charismatic and energetic even in later years, his social skills were second to none. Not only could he strike up a conversation with a random stranger, but he could also get their contact info and perhaps form a long-term friendship–and remarkably, he could do all of this inbetween sips of his morning coffee. He was Malcolm Gladwell’s concept of the “connector” personified.

I always considered him more of a pal than a teacher, but looking back on the time we spent together, he was one of the most influential mentors I ever had. His enthusiasm for art was contagious and instilled in me an appreciation for the same, from Lundeberg to Diebenkorn to Vlaminck to Pascin. Vic didn’t always have the easiest time imparting his wisdom. He once spent an entire morning trying to explain to me why Cézanne’s work was such a remarkable accomplishment. I was too dense at the time to grasp what he was saying, but it eventually sunk in.

He was one of the earliest supporters of my writing, and we spent months developing a story book together, which gave me the opportunity to see how skilled he was handling story and character. He prodded me for years to pursue writing seriously, and that too eventually sunk in. I remember during one visit I had brought my camera along and he asked me to take a photograph of him. The results were less than spectacular. The director in him emerged, and I received a firsthand taste of what he must have been like to work with on a live-action set. With the assured confidence of a master cinematographer, he directed me where to stand and where to point the camera, and he set himself up properly in the natural light. Within seconds, we had a fine portrait.

Thank you, Vic. For being a mentor, an inspiration, and a friend. It was an honor knowing you.

He is survived by his wife Monica, three children–Auguste, Cedric and Laila–and six grandchildren.